August 20th, 2025

“It is not enough to be busy. So are the ants. The question is: What are we busy about?” — Henry David Thoreau

Countless times in my career I have come across people and teams working inefficiently, being fully aware of this fact, and feeling unable to do otherwise.

They’re trapped in what I call “the illusion of progress”.

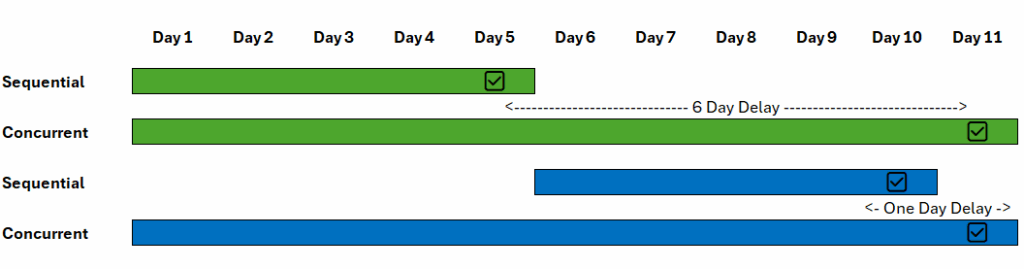

Imagine your team has been asked to do two projects, Project Green and Project Blue – each of which should be 5 days long, fully staffed. Both have been requested by important senior leaders, and they aren’t covered by any prioritization guidance.

The choice I see made more often than not is to do both at once. This lets you say to both senior leaders that the projects are making progress. Happy stakeholders make for a happy team, right?

There is a cost to context switching for complex tasks, though. Choosing to do both at once means that both projects take longer than they otherwise would, and both are delivered later than they otherwise would be. If you were to work on them consecutively Project Green would be delivered at the end of day 5. Project Blue would be delivered at the end of day 10.

Let’s walk through the example of working on them in parallel. We’ll use the 23 minute estimate for task switching cited by this Duke University article, and generously assume only one switch per day (mornings are for Green, and afternoons are for Blue). Realistically for complex work you’re likely having conversations and getting emails on both projects periodically, and more switching is happening than just this.

You’ve delivered Project Green 6 days after you might otherwise have finished it – and even Project Blue, which you started earlier, has been delayed by a day.

All you’ve gained is the ability to tell the Project Blue stakeholders that their work was in progress – at the cost of Project Green stakeholders actually having usable outcomes available to them for a week. (See below for an excellent Henrik Kniberg video demonstrating this.)

Looked at in this way, neither project’s stakeholders would appreciate the decision to put work in parallel that could otherwise have been sequenced.

When I walk through this example with people, a very common reaction I get is “I understand, but that just won’t work in my department” or “that isn’t realistic”.

Why not, I ask? Do your stakeholders prefer to get their work late? Do they not believe there is an efficiency penalty to task switching? Are they irrational?

Of course not… so given the clarity of research and simplicity of the math, why is this style of work still so prevalent?

- Fear: Teams fear political fallout from sequencing – so they choose to appease everyone superficially. Prioritizing one project over another might require an uncomfortable conversation with stakeholders, or might be seen as favoring one group over another, or the organizational culture doesn’t allow a response of “not yet” (much less “no”).

- Visibility vs. Value: People confuse looking busy with delivering value.

- Progress Theater: Recognition (and possibly rewards) are focused more on work launched than work completed.

Unsurprisingly, these are common symptoms of organizations with low psychological safety.

So what can be done to help overcome environments in which the most effective way of working (predictable, efficient and transparent) isn’t viewed as being an option? Let’s set aside the question of changing the culture for now (see more about that in Consciously Cultivated Culture as a Strategic Advantage) and focus on a smaller goal.

Prioritization. As mentioned in Prioritization: Killing Failed Projects Before They Start, having a clear process for valuing work and understanding the relative priority of work can empower teams to make smart decisions about staffing and sequential working.

Be Explicit about Opportunity Cost. When pressed to start your Project Blue while Project Green is still going on, make sure the opportunity cost is communicated. It may not be clear to the requester what will be slowed down or put aside to introduce new work. If they don’t have that information, they can’t make a fully informed decision about their need. Frame this conversation in stakeholder language. Instead of saying “we’ll be less efficient” say “If we start Project Blue before delivering Green, business outcomes for both will be delayed.”

Use Data, Not Just Logic. When possible, gather metrics on how long tasks actually take under multitasking vs sequencing in your team. Even a lightweight measurement (e.g., average cycle time per task in parallel vs sequential work) can provide proof beyond theory. Leaders tend to respond more to organizational data than abstract theory.

The “illusion of progress” is comforting, but it’s also costly. Splitting attention across competing priorities may appease in the moment, but it delays value, amplifies stress, and quietly erodes trust. What stakeholders truly want is not to see motion, but to see meaningful results.

Breaking free of this pattern requires courage: courage to prioritize, courage to say “not yet,” and courage to measure outcomes instead of appearances. The reward is not just faster projects – it’s a culture where progress is real, visible, and sustainable.

Or, as Thoreau might remind us: anyone can be busy – it only matters if that busyness is accomplishing something.

Tell Me More (Additional Reading)

- Deep Work – Newport

- Make Time – Knapp, Zeratsky

- Indistractable – Eyal